Handel blog 5*

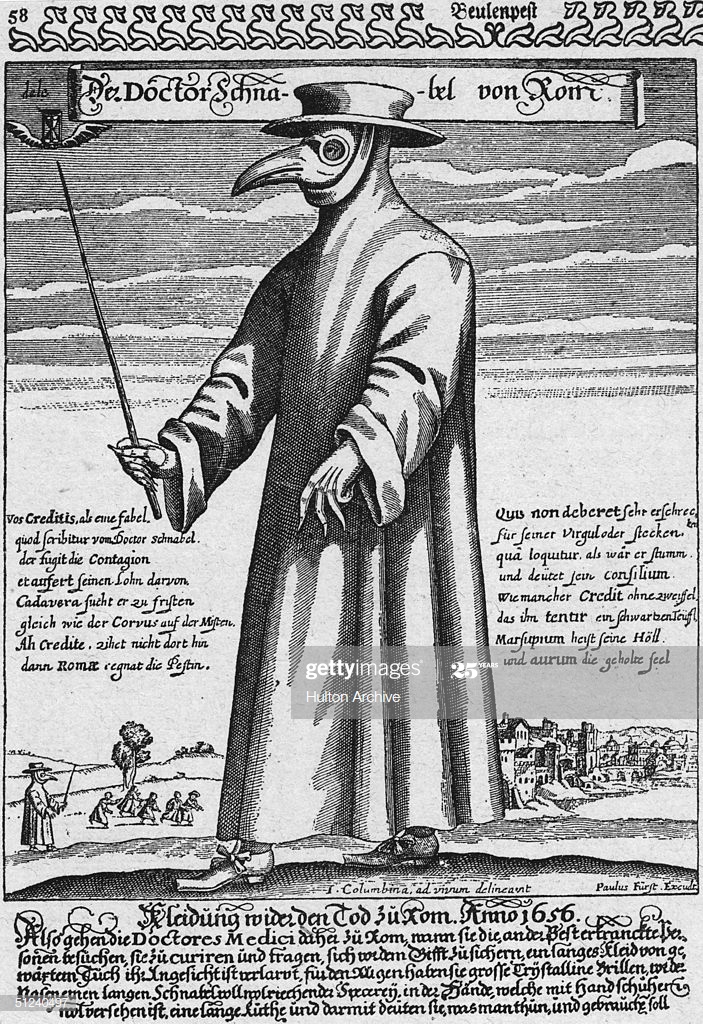

From Katherine: This isolation is definitely beginning to be irksome, even to an introvert like me. The practice of quarantining people who have a contagious illness and requiring people who are well to isolate themselves is one that became common as the Plague swept through parts of Europe in the mid-1600s, shortly before Handel was born in 1685. It did help in bringing an end to the spread of the Plague, though that disease was quite different from the current COVID-19. One of Handel’s most famous arias voiced a longing for freedom—“Lascia ch’io pianga.” Or, as the opening words translate: “Let me weep over my cruel fate and sigh for freedom.” The aria is from Rinaldo, but the beautiful melody is the one our Lydia first heard while Handel was still in Hamburg, before he went to Italy. Then it became the song she most associated with Handel: “Lascia la spina—leave the thorn but take the rose. Such a beautiful piece.” (p. 509) I guess its message–that we should try to avoid the bad and grasp what is good and beautiful–is timely.

From Clara: I remember trying to play that melody on my cello back when we first talked about it. The more popular words from Rinaldo were actually the ones sung by the castrato Farinelli in the movie—remember, where Handel supposedly faints from the sheer beauty of hearing Farinelli sing the aria. I found a clip of him singing it. You can hear it here. A friend on campus told me that the voice in the movie was actually a combination of a soprano and tenor rather than a modern countertenor as you might expect. I may have to watch the movie again.

From Brad: Isn’t that the movie that had some pretty sexy scenes in it, at least at the beginning? Here’s some information on the film. I think I should be able to stream it to my TV. The night will not be wasted.

From Katherine: I may have to watch it as well. Thanks, everyone. Maybe we will have a collaborative movie review next time. Stay well.

*All posts listed as “Handel blog” are texts that use the fictional characters in my book The Handel Letters: A Biographical Conversation. As in that book, the posts will often reference things from Handel’s life or time period as starting points. And the post will cite a page or paragraph in the book when it seems relevant. Find The Handel Letters.